Sometimes we don’t care to see underneath the hood of a one-line regression formula. Yet, it is incredibly powerful understand the reasons for why you set variables and tune parameters for analysis; many statistical assumptions and mathematics are glazed over by just typing out the code.

For example, many people think that the line that cuts through the middle of points, but little do they know that the ordinary least squares line is the most orthogonal to all the points. Anyways, today, I have decided to show what exactly the lm() and summary() functions are doing in the background! I believe that understanding the mechanics will increase awareness and appreciation of how truly amazing regression analysis is..

I guess there won’t be any specific packages comment on because this is all matrix algebra! Let’s begin with a previous diamonds dataset that I’ve suggested. Not the embedded one; that may be a little too big. It’s a smaller dataset provided by Texas A&M.

library(tidyverse)

url <- "https://ww2.amstat.org/publications/jse/v9n2/4Cdata.txt"

# read in and quick clean

data <- read_table(url, col_names = FALSE)

glimpse(data)

data <- data[,c(1,5)]

colnames(data) <- c("carat","sale")

rm(url)

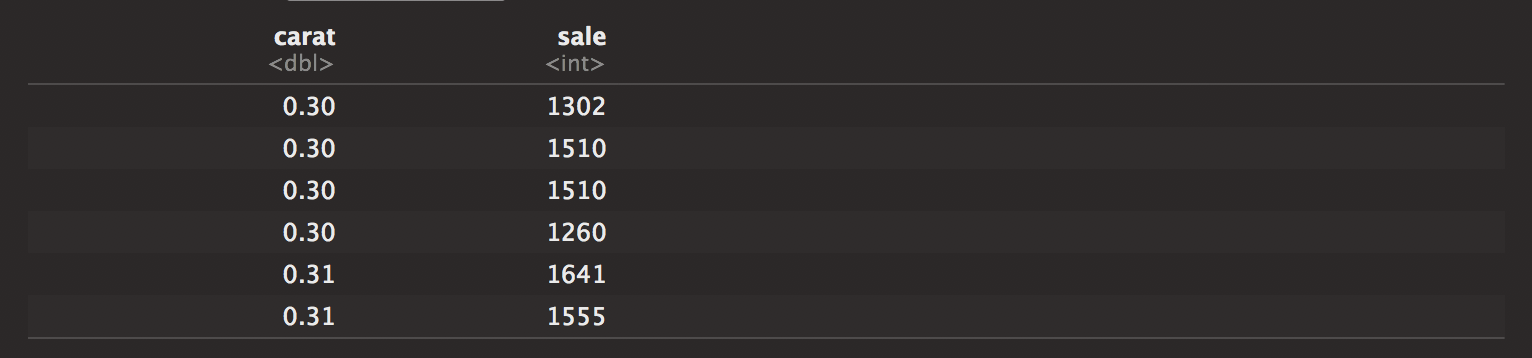

head(data)

Okay, that was just simple cleaning. Let’s just say that the carat amount is our explanatory variable, and the sale is our response. Putting this through our linear model, we see this here.

out.carat <- lm(sale ~ carat,data=data)

summary(out.carat)

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) -2298.4 158.5 -14.50 <2e-16 ***

## carat 11598.9 230.1 50.41 <2e-16 ***

##

## Residual standard error: 1118 on 306 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.8925, Adjusted R-squared: 0.8922

## F-statistic: 2541 on 1 and 306 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

Our output is as follows. The carat amount seems to be a significant effect that has a beta coefficient of 11598.9. Some glaze over the other details, but they are all important details that go into our eventual outputs.

Now, we see how simple that was but let’s dissect this dataset and see what we can do!

Doing regression by hand, we assume that data comes in (x.y) pairs. For this simple case, the formula is y ~ ß˚ + xß1 + ε, ε ~ N(µ,ø) (Where epsilon is normally distributed). Taking into consideration the error, we see that correlation coefficient affects every x,y pair.

For this dataset, we have known x’s and known y’s. Yet, we don’t have any of the other information. Let’s start with getting the beta coefficient, “11598.9”. The equation for the beta-hat coefficient for carat is given by this notation (x’x)^(-1)(x’y).

The apostrophes stand for transpose which is done with t(). The inverse is done with matrices, by the solve() function. Now, we will create the x and y matrices so we can find the ß1 coefficient or the “Estimate”. The x matrix is created by putting a 1 in the first row and the explanatory variable in the next. This is because the 1 stands for the “no effect” or the intercept estimate value. Other interesting matrix details include having to multiply left to right in the correct order and using %*% instead of the usual *.

# x matrix given by 1 and carat

x <- cbind(1,data$carat) %>% as.matrix()

# y matrix given by the sale

y <- data$sale %>% as.matrix()

# finding beta hat

behat <- solve(t(x)%*%x)%*%(t(x)%*%y)

behat

## -2298.358

## 11598.884

As you see here, we have the same exact values as the lm output! Now we can try getting the standard errors. The standard error is given by the square root of the s^2 value times the appropriate diagonal element of the (x’x)^(-1) matrix. When I say diagonal, it is just the diagonal of the correct column. s^2 is given by t(y-x%*%behat)%*%(y-x%*%behat)/(n-k) and is the sum of the squared deviations around the mean with a correctional factor of the degrees of freedom.

# number of columns in x matrix

k <- ncol(x)

# number of rows in x matrix

n <- nrow(x)

# degrees of freedom

df <- n-k

# RSS or RSE

rss <- t(y-x%*%behat)%*%(y-x%*%behat)

# finding s^2

ssquared <- t(y-x%*%behat)%*%(y-x%*%behat)/df

# Calculating SE

invmatrix <- solve(t(x)%*%x)

# intercept is first diagonal

intercept <- sqrt(ssquared*invmatrix[1,1])

# carat

carat <- sqrt(ssquared*invmatrix[2,2])

c("intercept" = intercept, "carat" = carat)

## intercept carat

## 158.5306 230.1106

Here we go. We can see that these are the same exact values! Let’s keep going. Other important values that may be necessary might be the p-values and test statistic. We’ll do just the t statistics even since we aren’t doing an anova. I don’t think I want to go through the trouble of creating full and reduced models. It may make more sense with more columns. Technically though, the f statistic is conceptually the same thing as the t, just a likelihood ratio test. From our test statistic, we can use a table value or a shortcut pf() or pt() for our p-values.

# t value for intercept

int <- behat[1,1]/intercept

# t value for carat

car <- behat[2,1]/carat

# calculating p-values

ptint <- pt(int,df)

ptcar <- pt(50.41,df)

c("intercept t"=int,"carat t" = car, "pval int" = ptint, "pval car" = ptcar)

## intercept t carat t pval int pval car

## -14.49788 50.40569 6.403993e-37 0.000000e+00

I actually think that there is something wrong I did with the carat p-value. I have to correct that and figure it out. Regardless, our output seems to reflect that of our linear model! Doing this by hand will take a good hour. This one may not be so bad because it is the simple linear case, but there are so many rows! We gotta be grateful for computing power.

Now from here, a prediction is easy to make. It’s just plugging in an x value to our model. Let’s compare.

# predicted carat value .5

ppv <- .5

# coded value

lmpred <- predict(out.carat,newdata=data.frame(carat=ppv))

# computed value y = ß˚ + xß1 + ε

intcpt <- behat[1,1]

beta <- behat[2,1]

cmpred <- intcpt + ppv*beta

# output

c("lm" = lmpred, "matrix" = cmpred)

So, we see that it is not so difficult to do the math with code. Neither is it difficult to do by hand, but it might be nice to do it on the computer. Of course, to some it is useless but for myself, it is extremely important! Just knowing the mechanics of regression allows me to see when it is infeasible to do certain types of basis function expansions, what creates a singular matrix, and what thresholds yield more power for prediction!

Overall, this is just a small introduction, but an important way to understand the mechanics of regression analysis. This can be extended to larger cases. Of course, this is much different from working with logistic regression datasets. That will prove to be more of a challenge. There is more power in understanding what exactly you are doing!