You are at a party with 50 people, each with one half of a raffle ticket in their hand. As for the other half, everyone in the room has been instructed to write down only their first and last initials. You’re probably the only one eyeing the prize (it’s just a nice wooden box of some sweet scented candles, but the reason why you want it is because you forgot to buy your wife a birthday present and tomorrow is the day!). As the time approached for the organizer to close the event, he announced the winner of the raffle.

“The winner of this raffle is…. T.W.!” “T.W.? Really? What are the odds? (it’s actually 0.02) that’s me!”

Quickly jumping up to claim your prize, you take one step forward and realize that some dude in front of you is blocking your path. You watch him, askew, as he walked up to the podium to receive his prize. Bewildered, you ask him:

“Sir, I think you’re mistaken. What is your name?” “Tiger Woods. Don’t you know who I am?”

You tilt your head and wonder. Not how this happened, but how poorly designed this lottery system is. You’re going to have to get your wife something special on the way back home.

What really is the probability of someone having the same exact initials as you in a room of 50 people? It has to be quite small. There are 26 choices for the first letter, then 26 choices for the second letter. This would end up to be 26 X 26 or 26^2 totalling 676 different possible combinations. For two people to have the same initials, the probability has to be rather slim, right?

Not necessarily.

In this situation, we are looking for probability of pairs, not of individuals. The math looks like this:

- Let’s say P(A) (probability of A occuring) is the same as saying the probability of there actually being a matching initial.

- Since the total sample space equals one… One minus the probability of there being no pairs of people should give us the answer.

- Since we assume independence, of we were to number the people from 1:50 the event that all 50 people have different initials = (1/676)^50 X (676 X 675 X … X 626)

- The same as the event that each person doesn’t have the same initials as the next individual until we get to 50.

If we simplify the math, it will look like this:

# We can't use !, so we use the function factorial()

( factorial(676) / factorial(676-50) ) / ( 676^50 )

Yet, unfortunately in R, we have to get a little creative as our calculations exceeded the limits on implementation (plus, you have to use factor() but that still doesn’t work).

Great thing is, we can use the choose() function instead to get the probability that no 2 people have the same exact initials.

1 - ( factorial(50) * choose(676,50) ) / ( 676^50 )

## [1] 0.1559757

Wait, a 16% chance that 2 people DO NOT have the same initials? This means that the probability of 2 individuals having the same initial first and last name will be 84.4%. Wow, a lot more likely than I thought (I guess I can’t blame Tiger for having my initials).

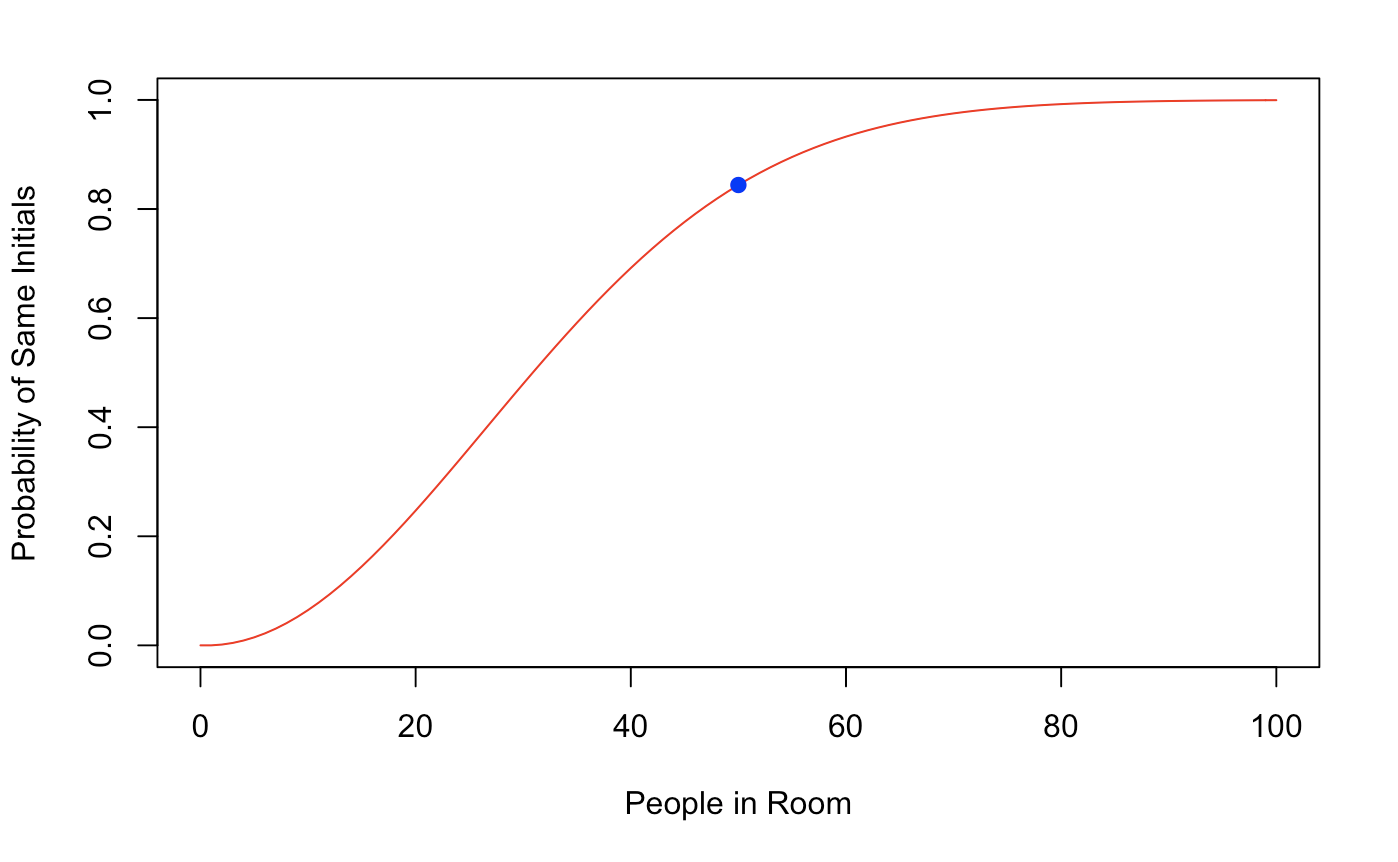

If we were to graph this outcome for n (number of people in a room) of 0:100 people, we will see this.

initials <- function(n){

1 - (factorial(n) * choose(676,n))/(676^n)

}

n <- seq(0,100)

exact <- sapply(n,initials)

plot(n,exact,col ='red',

type ='l', xlab ='People in Room',

ylab ='Probability of Same Initials')

points(50,1 - 0.1559757,col = "blue", pch = 19)

The S curve tells us that at some number n, we will approach 100%. Of course, we aren’t tossing out the possibility that every person has a unique set of initials that no one else has.

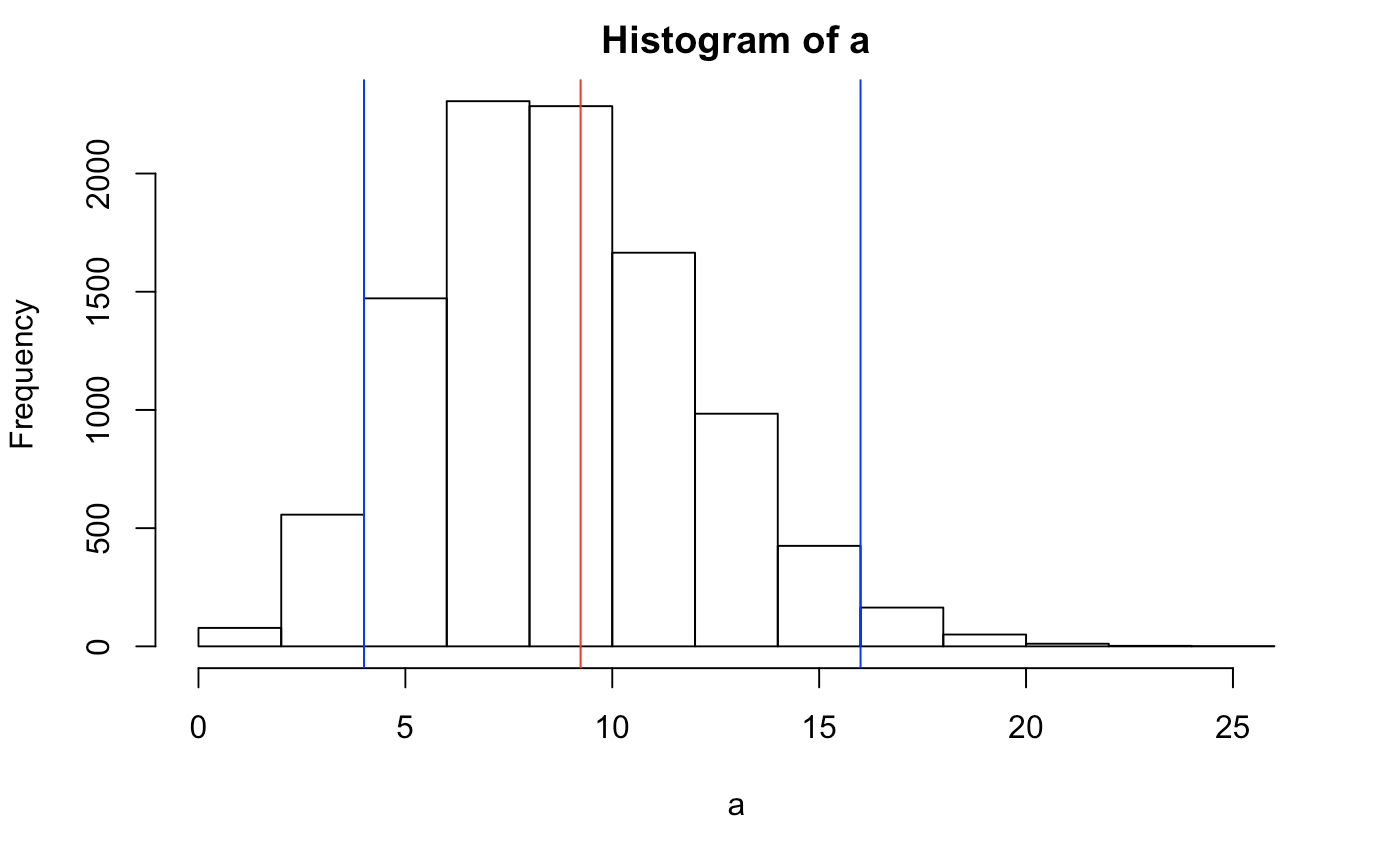

Hold on a minute, if the probability is so high, how likely is it that the person next I ask has the same initials? How many people do I have to ask on average to find the next person that has the same initials as me? Let’s do a bit more calculations.

# using a monte carlo sample of 10000 iterations of a negative binomial

a <- rnbinom(10000,50,1 - 0.1559757)

b <- quantile(a,c(.025,.975))

c <- mean(a)

hist(a)

abline(v = b, col = "blue")

abline(v = c, col = "red")

c("lower" = b[1], "average" = c, "upper" = b[2])

## lower.2.5% average upper.97.5%

## 4.0000 9.2348 16.0000

So, on average, about the 9th person you ask in this room will most likely have the same initials as you! Of course, this is under the assumption that the distribution of initials is normal ( which it isn’t ). Maybe if your initials were more common.. Yet a good enough estimate. To be honest, it would be more common for someone to have more matches just because the population is skewed. If I pulled out data of the frequencies of first and last initials in the US then attach probabilities associated with each of the letters, weighted probabilities could be used to come up with more accurate numbers.

You may have picked up on it, but this is actually a widely known problem that has been applied many times. The real nickname is called the “birthday problem”. We extend the situation of the same initials to birthdays (month and date combinations, of course..), but instead of 676 possible choices, we end up with 365 (excluding leap year). This problem has far applications to lottery winnings, class phenotype probability, marketing, and even more. Just know that it’s been thought about a lot and I am not the one introducing it to you for the first time.

Anyways, thank you for joining! I hope this helps you feel a bit more informed..